平山論文日本語訳(翻訳: Googl翻訳)

目次

喫煙者で喫煙しない妻は肺がんのリスクが高い:日本の研究

Takeshi Hirayama

概要

日本の 29 の保健所地区で行われた研究では、40 歳以上の非喫煙者 91,540 人が 14 年間 (1966 ~ 79 年) 追跡調査され、夫の喫煙習慣に応じて肺がんの標準化された死亡率が評価されました。重度の喫煙者の妻は、肺がんを発症するリスクが高いことが判明し、用量反応関係が観察されました。夫の喫煙と妻の肺がん発症リスクとの関係は、夫の年齢別、職業別に分析すると同様のパターンを示した。登録時に夫が 40 歳から 50 歳の場合、このリスクは農業家族で特に大きかった。夫の喫煙習慣は、妻が胃がん、子宮頸がん、虚血性心疾患などの他の病気で死亡するリスクに影響を与えませんでした。

夫の飲酒習慣は、肺がんを含む妻の死因に影響を与えないようでした.

これらの結果は、受動喫煙または間接喫煙が肺がんの原因因子の 1 つとして重要である可能性を示しています。彼らはまた、女性自身が非喫煙者であるにも関わらず、なぜ多くの女性が肺がんを発症するのかという長年の謎を説明しているようです. これらの結果は、喫煙者を非喫煙者と比較することによって、喫煙者の肺がん発症の相対リスクを評価するという実践にも疑問を投げかけています。

序章

たばこの副流煙や間接喫煙には発がん性物質を含むさまざまな有毒物質が含まれているため、たばこに長期間さらされること(受動喫煙)が非喫煙者の健康に及ぼす可能性のある影響を徹底的に研究する必要があります。1 2そのような研究の必要性は、たばこの煙に慢性的にさらされている非喫煙者における小気道機能障害の報告によって増加しました。3

肺がんに対する受動喫煙の影響は、40 歳以上の非喫煙主婦 91,540 人を追跡し、夫の喫煙習慣に応じて肺がんを発症するリスクを測定することによって研究されました。

メソッド

喫煙、飲酒、職業、婚姻状況などの要因の健康への影響を研究するために、1965 年秋以来、日本の 6 都道府県の 29 の保健所地区で前向き人口調査が進行中です。合計で 265 118国勢調査人口の 91-99% にあたる 40 歳以上の成人 (男性 122,261 人、女性 142,857 人) にインタビューを行い、その後、特別年次国勢調査によって得られた居住者リストである危険因子記録間の記録リンク システムを確立しました。 、および死亡証明書。

この研究におけるタバコの直接喫煙の影響はすでに報告されているので、4-7私の研究は非喫煙の妻の肺がんリスクに対する夫の喫煙の影響に焦点を当てた. このような観察が可能になったのは、この研究の開始時に、喫煙習慣を含むライフスタイルに関する詳細な質問が夫と妻に個別に尋ねられたためです。したがって、主観的なバイアスは考えられませんでした。

14 年間の追跡期間中 (1966 年から 1979 年) に、合計 346 人の女性の肺癌による死亡が記録されました。これらの女性のうち 245 人は既婚者であり、そのうち 174 人は非喫煙者でもありました。これらの症例は、夫の喫煙習慣が調査された 91,540 人の非喫煙の既婚女性で発生しました。肺がんのリスクは、考えられる交絡変数を考慮して慎重に測定されました。

結果

重度の喫煙者の妻は、非喫煙者の妻よりも肺がんを発症するリスクが高いことが判明し、統計的に有意な用量反応関係が観察されました (Mantel-extension c検定の結果は 3 . 299; 両側 p = 0 . 00097)。肺がんの年齢職業標準化年間死亡率は 8でした。7/100 000 (21 895 のうち 32) の夫が非喫煙者または時折喫煙者だった場合、14 . 夫が元喫煙者または毎日 1 ~ 19 本のタバコを吸っていた場合は 0 (44,184 のうち 86)、夫が毎日 20 本以上のタバコを吸っていた場合は 18-1 (25,146 のうち 56) でした。これらの数値は、リスク比 1 を示しています。00、1 。61、および2.それぞれ08。同様の傾向は、夫の年齢層と職業群でも観察された(表I)。

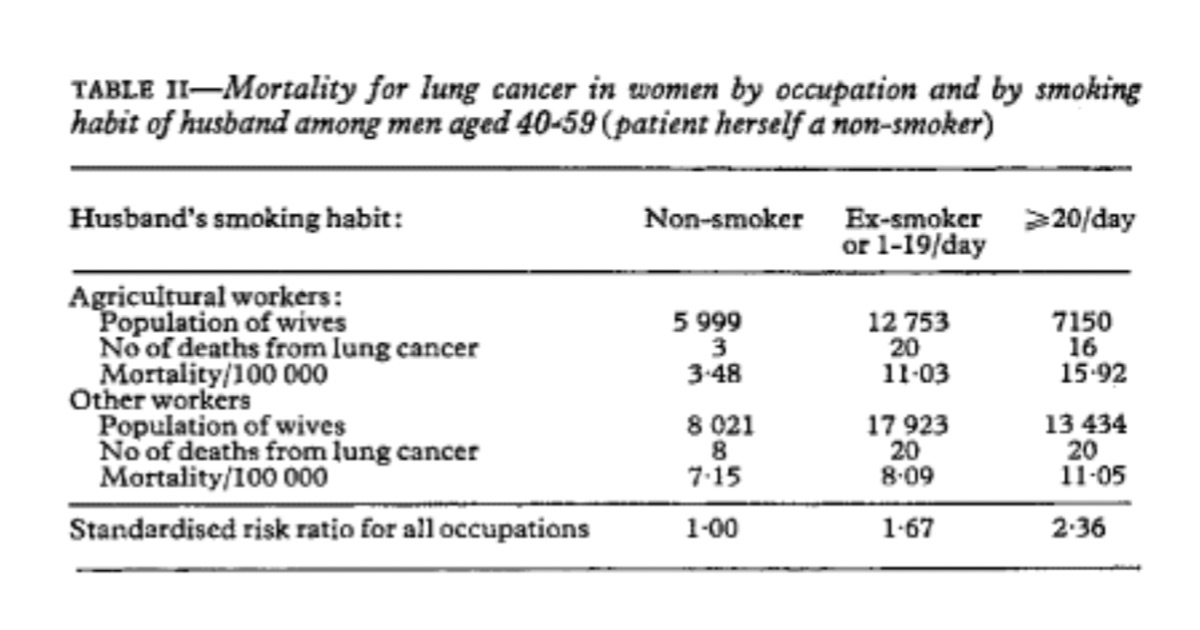

夫の喫煙習慣と妻の肺がん発症リスクとの関係は、夫が登録時に 40 ~ 59 歳の農家で特に有意でした (Mantel-extension chi は 2 . 597 または両側 p=0 . 0094) 。 ; 肺がんのリスク比は 1でした。00、3 。17、および4.57 夫が非喫煙者または時々喫煙する場合、元喫煙者または毎日 1 ~ 19 本のタバコを吸う場合、および毎日 20 本以上のタバコを喫煙する場合 (表 II )。

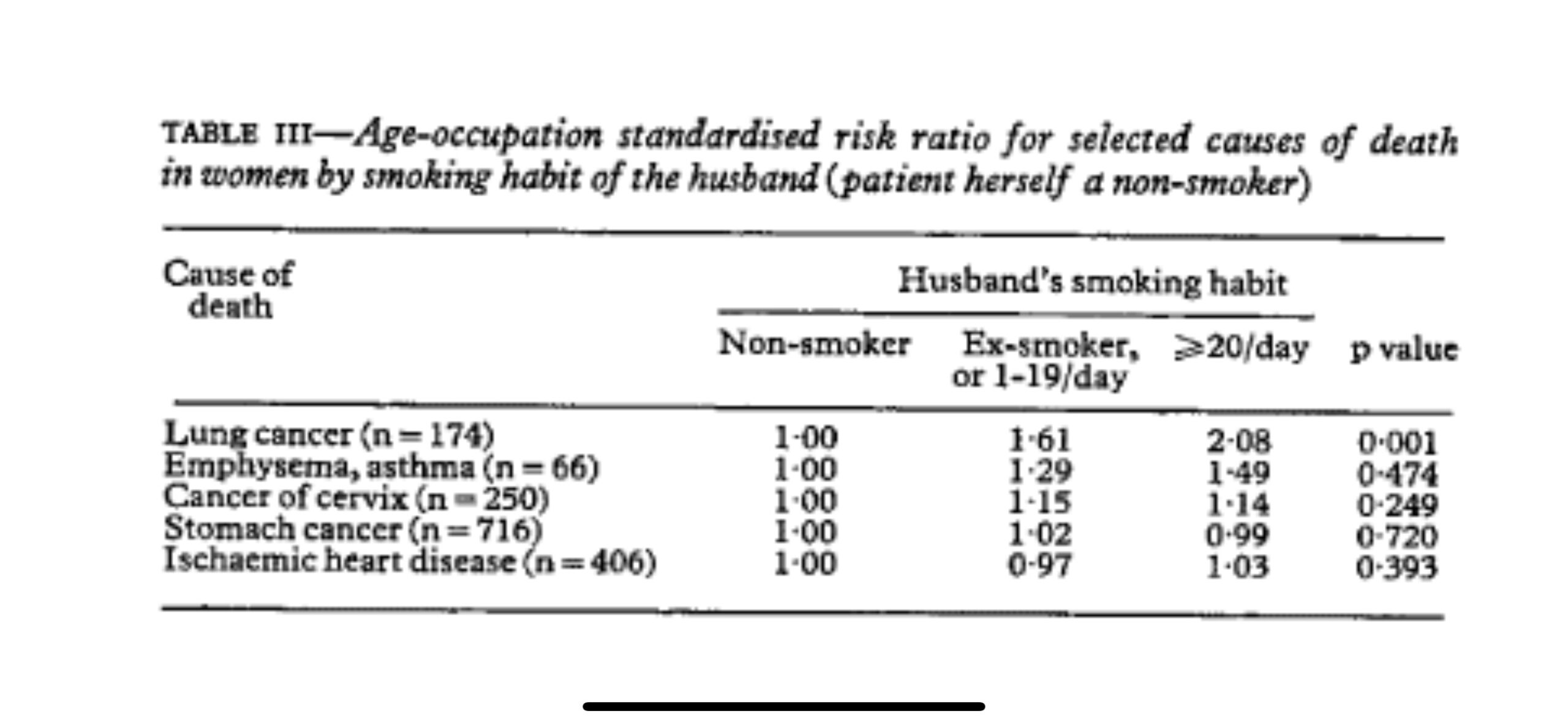

夫の喫煙習慣は、妻が他の主要な胃がん (n=716) や子宮頸がん (n=250)、虚血性心疾患 (n=406) を発症するリスクに影響を与えないようでした。肺気腫と喘息を発症するリスクは、喫煙者の非喫煙者の妻で高いように見えましたが、その効果は統計的に有意ではありませんでした (表 III )。

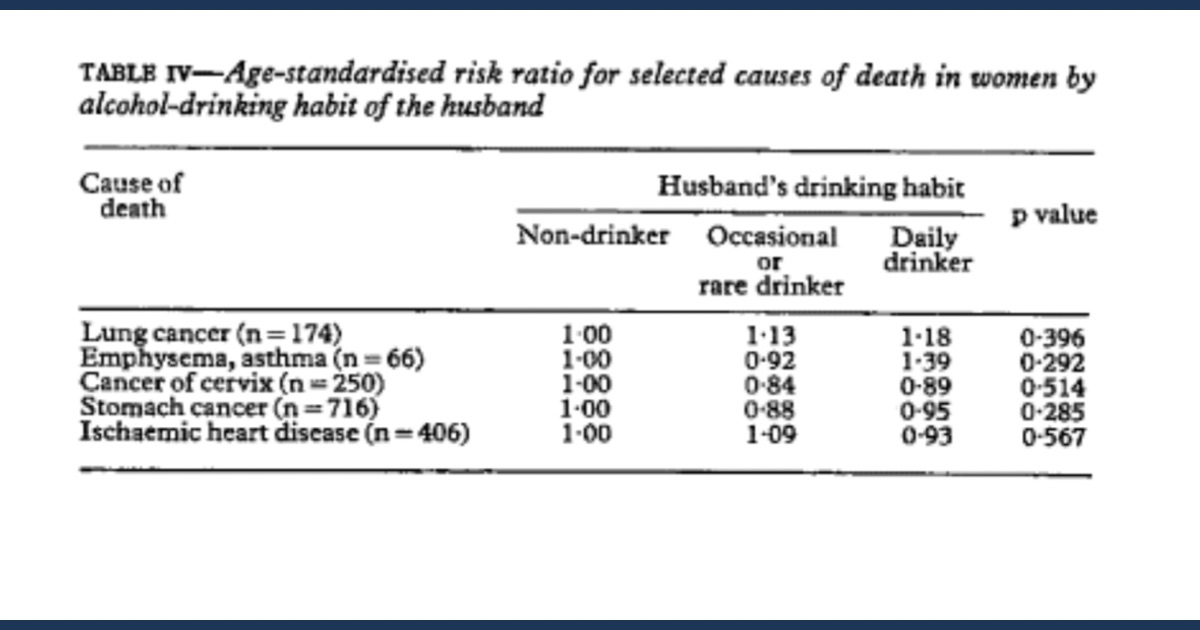

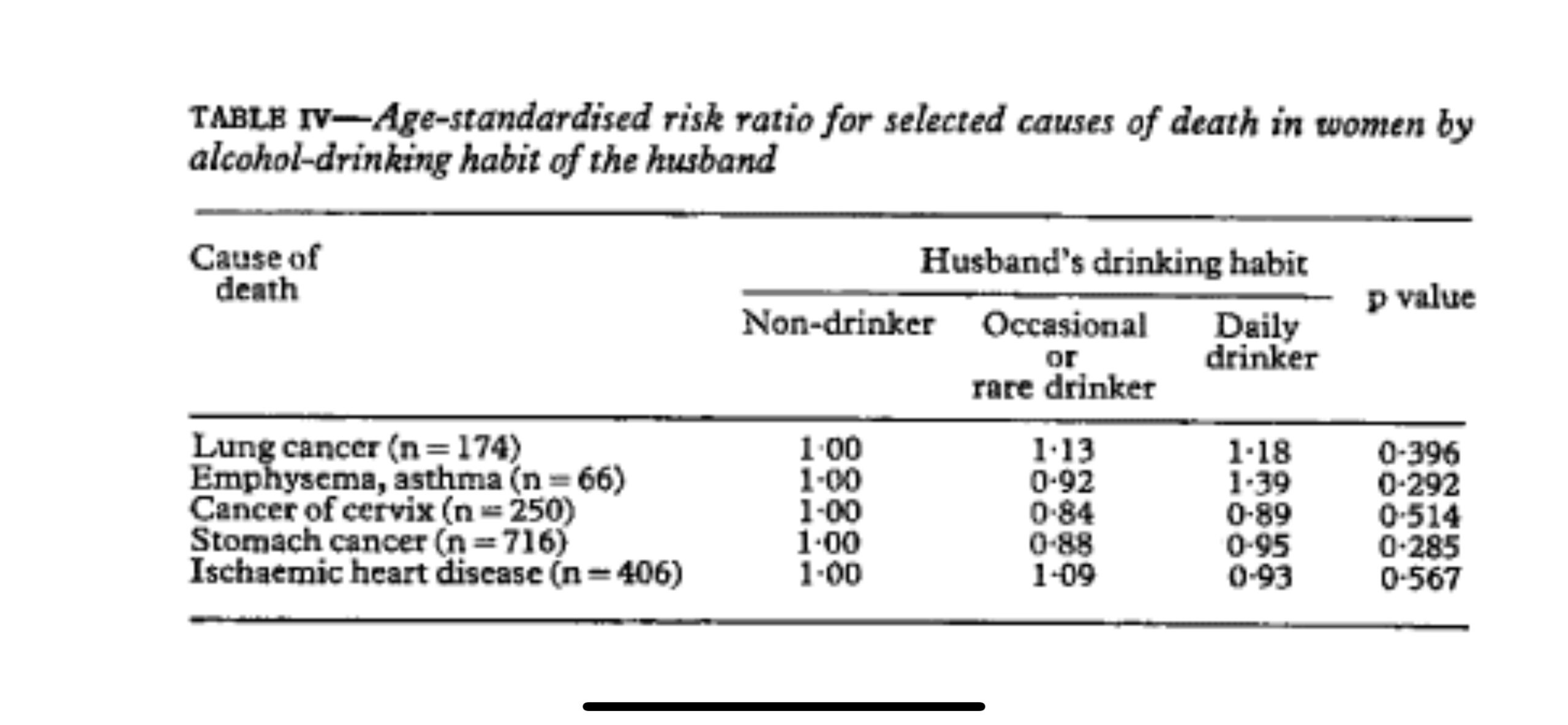

飲酒習慣などの夫のその他の特徴は、妻の肺がんによる死亡率に影響を与えませんでした。肺がんによる死亡の相対リスク比は 1でした。00、1 。13、および1.18 (p= 0.396 ) 夫が非飲酒者、時折またはまれに飲酒者、毎日飲酒者の場合。他の死因についても同様の結果が見られました (表 IV )。

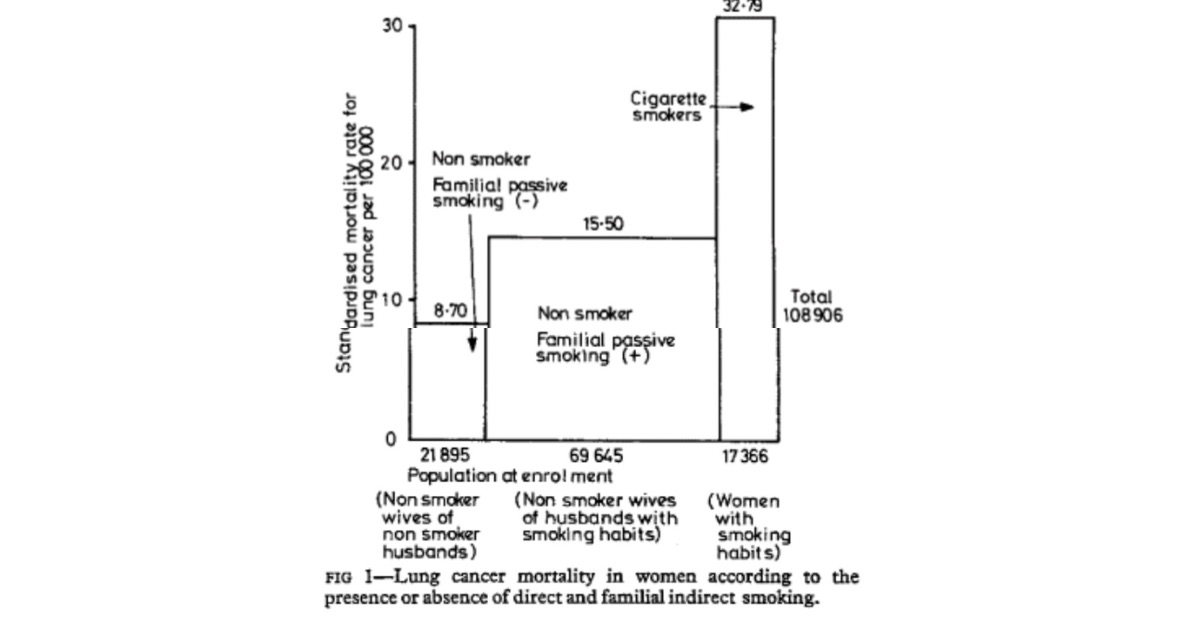

最後に、受動喫煙の効果を直接喫煙の効果と比較しました。受動喫煙の影響は、直接喫煙の約 2 分の 1 から 3 分の 1 でした。受動喫煙による肺がん発症の相対リスクは約1でした。約 3 と比較して 8 。直接喫煙者では 8 (図 1 )。

討論

受動喫煙の可能性のある影響は、夫がさまざまな喫煙習慣を持っている多くの非喫煙妻を追跡し、肺がんを発症するリスクを測定することによって研究されました. 夫の喫煙にさらされ続けると、非喫煙者の肺がんによる死亡率が最大 2 倍に増加しました。癌を発症するリスクの増加の程度は 4 に達した。1 日 20 本以上のたばこを吸う 40 歳から 59 歳の農業従事者の非喫煙妻の 6。

統計的に有意な関係 (両側 p=0 .00097) 夫の喫煙量と喫煙していない妻の肺癌死亡率との差は、これらの発見が偶然の結果ではないことを示唆しています。このような影響が肺がんに限定されているかどうかを判断するために、他の死因について同様の研究が行われました。夫の喫煙習慣と妻の肺気腫や喘息による死亡との間には関係があるように見えたが、受動喫煙の影響は肺癌で最も強かった。受動喫煙は、胃がん、子宮頸がん、または虚血性心疾患を発症するリスクを増加させるようには見えませんでした. 妻の死亡率に影響を与える夫の唯一の習慣は喫煙であることがわかりました。例として、夫の飲酒習慣が妻の死亡率に影響しないことが示されました。

最も重要な交絡変数は、都市要因でした。したがって、同様の観察が農業家族と非農業家族で行われ、同様の用量反応関係が両方のグループで観察されました。受動喫煙の影響は、農業家族の若いカップルで最も顕著であり、相対リスクは 4.6 に達しました。これはおそらく、農村居住者の場合、家族以外で受動喫煙にさらされる程度が少ないためです。ヘビースモーカーの夫を持つ妻の非喫煙率が都市部の家庭で農村部の家庭よりも低いことは不可解だが、農村部の家庭では夫婦の相互接触の期間が長いことを反映していると思われる. 都市部の家庭では、1 日の短い時間しか会わないカップルもいます。

最後に、受動喫煙の影響を直接喫煙の影響と比較しました。結果は、受動喫煙の影響が、死亡率または相対リスクの点で直接喫煙の約 2 分の 1 から 3 分の 1 であることを明確に示しました。しかし、寄与リスクに関しては、女性の肺がんに対する受動喫煙の影響は、直接喫煙よりもはるかに重要であるに違いありません (図 1 )。煙。したがって、間接喫煙の相対リスクは直接喫煙よりも小さかったが、受動喫煙による肺がんによる絶対的な過剰死亡は、被ばくしたグループのサイズが大きいため重要であるにちがいない。

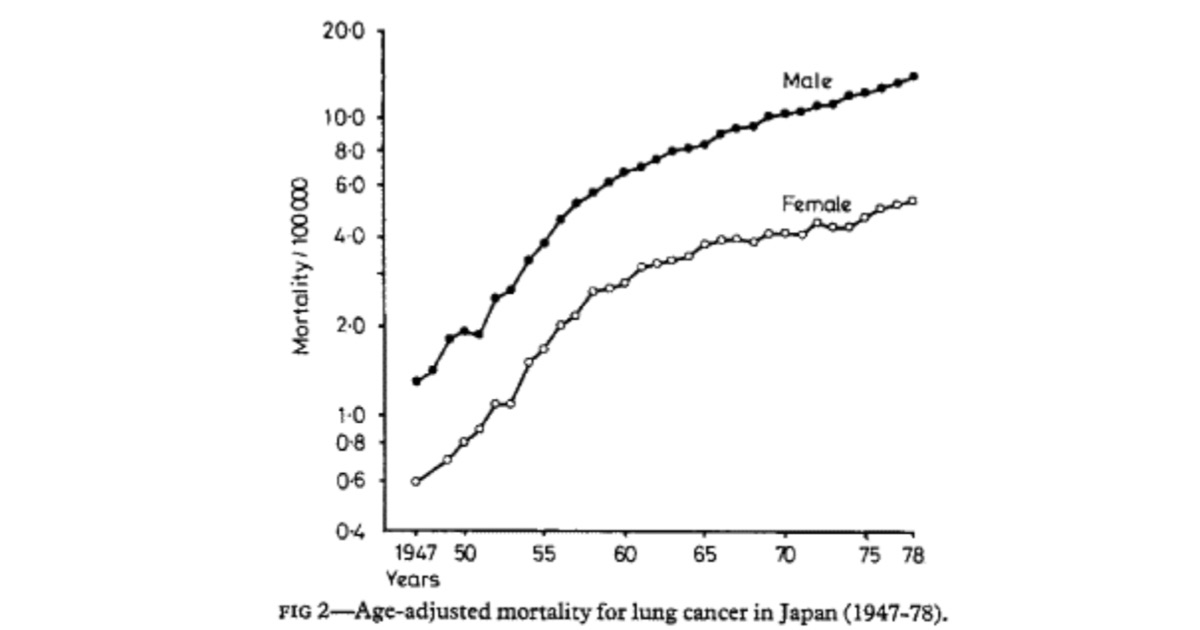

肺がんの年齢調整死亡率は、日本では男性と女性の両方で急激に増加しています (図 2 )。肺がんの日本人女性の喫煙者はごく一部にすぎないため、肺がんによる女性の死亡率が男性の死亡率と類似している理由は不明です。今回の研究は、この長年の謎の少なくとも一部を説明しているように見える.

この観察結果は、喫煙者を非喫煙者と比較することによって、喫煙者の肺がん発症の相対リスクを評価する従来の方法の有効性にも疑問を投げかけています。この研究は、非喫煙者は均質なグループではなく、以前に間接喫煙または受動喫煙にさらされた程度に応じて細分化する必要があることを示しています。

この作品は、厚生省のがん研究費補助金によって支援されました。

参考文献

1 Brunnemann KD、Adams JD、Ho DPS、他。タバコの煙が室内雰囲気に与える影響。Ⅱ.メインエイド副流煙中の揮発性およびタバコ特有のニトロソアミンと室内汚染へのそれらの寄与。中:環境汚染物質の感知に関する第 4 回 Foint 会議の議事録。New Orleans 1977. Washington: American Chemical Society, 1978:876-80.

2ブルネマン KD、ホフマン D. タバコの煙に関する化学的研究 LIX。タバコの煙および汚染された室内環境中の揮発性ニトロソアミンの分析。中: Waler EA、Griciute L、Castegnaro M、編。N-ニトロソ化合物の環境側面。(IARC の科学出版物 No 19) Lyons : WHO、1978:343-56。

3ホワイト RJ、Froeb FH。たばこの煙に慢性的にさらされている非喫煙者における小気道機能不全。N Engl F Med 1980;302:720-3。

4 Hirayama T. 日本の国勢調査人口に基づくがん疫学に関する前向き研究。In: XI International Cancer Congress の議事録。フィレンツェ。Cancer Epidemiology and Environmental Factors、3. アムステルダム: Excerpta Medica、1975:26-35。

5 Hirayama T. 集団研究に基づく肺がんの疫学。In:大気汚染研究の臨床的意義。シカゴ: アメリカ医師会、1976:69-78。

6平山徹. 喫煙とがん. 日本の国勢調査人口に基づくがん疫学に関する前向き研究。中: 1975 年の喫煙と健康に関する第 3 回世界会議の議事録。ワシントン: 保健教育福祉省、1977:65-72。(DHEW 発行番号 (NIH) 77-1413。)

7 Hirayama T. 日本の国勢調査人口に基づくがん疫学に関する前向き研究。に: ニーブルグ HE、編。がんの検出と予防に関する第 3 回国際シンポジウム。Pt 1. Vol 1. ニューヨーク: Marcel, Dekter, 1977:1139-48.

(1980 年 11 月 13 日受理)

国立がん研究センター 東京都 国立がん研究 センター疫学部長

平山健

以下英語文

Non-smoking wives of heavy smokes have a higher risk of lung cancer: a study from Japan

Takeshi Hirayama

Abstract

In a study in 29 health centre districts in Japan 91 540 non-smoking wises aged 40 and above were followed up for 14 years (1966-79), and standardised mortality rates for lung cancer were assessed according to the smoking habits of their husbands. Wives of heavy smokers were found to have a higher risk of developing lung cancer and a dose-response relation was observed. The relation between the husband’s smoking and the wife’s risk of developing lung cancer showed a similar pattern when analysed by age and occupation of the husband. The risk was particulary great in agricultural families when the husbands were aged 40-50 at enrolment. The husband’s smoking habit did not affect their wives’ risk of dying from other disease such as stomach cancer, cervical cancer and ischaemic heart disease. The risk of developing emphysema and asthma seemed to be higher in non-smoking wives of heavy smokers but the effect was not statistically significant.

The husband’s drinking habit seemed to have no effect on any causes of death in their wives, including lung cancer.

These results indicate the possible importance of passive or indirect smoking as one of the causal factors of lung cancer. They also appear to explain the long-standing riddle of why many women develop lung cancer athough they themselves are non-smokers. These results also cast doubt on the practice of assessing the relative risk of developing lung cancer in smokers by comparing them with non-smokers.

Introduction

The possible consequences to the health of non-smokers of long-term exposure to cigarette (passive smoking) should be studied thoroughly because the side-stream and second-hand smoke of cigarettes contain various toxic substances, including carcinogens. 1 2 The need for such a study increased by the report of small-airwais dysfunction in non-smokers chronically exposed to tobacco smoke.3

The effect of passive smoking on lung cancer was studied by following 91 540 non-smoking housewives aged 40 and above and measuring their risk of developing lung cancer according to the smoking habits of their husbands.

Methods

To study the consequences to health of such factors as cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, ocupation, and marital status, a prospective population study has been in progress in 29 health centre districts in six prefectures in Japan since the autumn of 1965. In total 265 118 adults (122 261 men and 142 857 women) aged 40 years and over, 91-99% of the census population, were interviewed and followed by establishing a record linkage system between the risk-factor records, a residence list obtained by special yearly census, and death certificates.

Since the effect of direct smoking of cigarettes in this study has already been reported,4-7 my study focused on the effect of husband’s smoking on the risk of lung cancer in their non-smoking wives. Such observation was possible since detailed questions about lifestyle, including smoking habits, were asked of husbands and wives independently at the start of this study. No subjective bias was therefore conceivable.

A total of 346 deaths from lung cancer in women were recorded during 14 years of follow-up (1966-79). Of these women 245 were married, and 174 of these were also non-smokers. These cases occurred among 91 540 non-smoking married women whose husbands’ smoking habits were studied. The risk of lung cancer was carefully measured, taking into consideration possible confounding variables.

Results

Wives of heavy smokers were found to have a higher risk of developing lung cancer than wives of non-smokers and a statistically significant dose-response relationship was observed (Mantel-extension c test result being 3.299; two-tailed p = 0.00097). Age-occupation standardised annual mortality rates for lung cancer were 8.7/100 000 (32 out of 21 895) when husbands were non-smokers or occasional smokers, 14.0 (86 out of 44 184) when husbands were ex-smokers or daily smokers of 1-19 cigarettes, and 18-1 (56 out of 25 146) when husbands were daily smokers of 20 or more cigarettes. These figures gave risk ratios of 1.00, 1.61, and 2.08 respectively. A similar trend was observed in age and occupation groups of husbands (table I).

The relation between the husband’s smoking habit and the wife’s risk of developing lung cancer was particulary significant in agricultural families when the husband was aged 40-59 at enrolment (Mantel-extension chi being 2.597 or two-tailed p=0.0094); lung cancer risk ratios were 1.00, 3.17, and 4.57 when husbands were non-smokers or occasional smokers, ex-smokers or smokers of 1-19 cigarettes daily, and smokers of 20 or more cigarettes daily respectively (table II).

The husbands’ smoking habits seemed to have no effect on their wives’ risk of developing other major cancers of the stomach (n=716) and of the cervix (n=250) or ischaemic heart disease (n=406). The risk of developing emphysema and asthma seemed to be higher among the non-smoking wives of smokers, but the effect was not satistically significant (table III).

Other characteristics of the husbands, such as their alcohol drinking habits did not affect mortality from lung cancer in their wives. The relative risk ratios of death from lung cancer were 1.00, 1.13, and 1.18 (p=0.396) respectively when husbands were non-drinkers, occasional or rare drinkers, and daily drinkers. Similar results were found with other causes of death (table IV).

Finally, the effect of passive smoking was compared with the effect of direct smoking. The effect of passive smoking was around one-half to one-third that of direct smoking. The relative risk of developing lung cancer by passive smoking was about 1.8 compared with about 3.8 in direct smokers (fig 1).

Discussion

The possible effect of passive smoking was studied by following many non-smoking wives whose husbands had various smoking habits, and measuring their risk of developing lung cancer. Continued exposure to their husbands’ smoking increased mortality from lung cancer in non-smokers up to twofold. The extent of the increase in the risk of developing cancer reached as high as 4.6 for non-smoking wives of agricultural workers aged 40-59 who smoked 20 or more cigarettes a day.

The fact that there was a stastitically significant relation (two-tailed p=0.00097) between the amount the husbands smoked and the mortality of their non-smoking wives from lung cancer suggests that these findings were not the result of chance. To determine whether such an effect was limited to lung cancer, similar studies were conducted with other causes of death. Although there seemed to be a relation between husbands’ smoking habits and deaths from emphysema and asthma in their wives, the effect of passive smoking was strongest with lung cancer. Passive smoking did not seem to increase the risk of developing stomach cancer, cervical cancer, or ischaemic heart disease. We found that smoking was the only habit of the husbands to affect wives’ mortality. The absence of an effect of husbands’ drinking habits on mortality in their wives was shown as an example.

The most important confounding variables would have been urban factors. Similar observations were therefore made for agricultural families and for non-agricultural families, and a similar dose-response relation was observed in both groups. The effect of passive smoking was most striking in younger couples in agricultural families, relative risk reaching 4.6, probably because of the lesser extent of the exposure to passive smoking outside the family in the case of rural residents. That the rate for non-smoking wives with husbands who were heavy smokers in urban families was lower than that in rural families is puzzling but probably reflects a longer period of mutual contact of couples in rural families. In urban families some couples meet only for a short period in the day.

Finally, the effects of passive smoking were compared with the effects direct smoking. The results clearly indicated that the effect of passive smiking is about one-half to one-third that of direct smoking in therms of mortality ratio or relative risk. In therms of attributable risk, however, the effect of passive smoking on lung cancer in women must be much more important than that of direct smoking (fig 1), especially in countries such as Japan where 73% of men but only 15% of women smoke. Therefore, although the relative risk of indirect smoking was smaller than of the direct smoking, the absolute excess deaths from lung cancer due to passive smoking must be important because of the large size of the exposed group.

The age-adjusted mortality rates for lung cancer have been sharply increasing both for men and for women in Japan (fig 2). As only a fraction of Japanese women with lung cancer smoke cigarettes, the reasons why their mortality from lung cancer parallels that in men have been unclear. The present study appears to explain at least a part of this long-standing riddle.

This observation also questions the validity of the conventional method of assessing the relative risk of developing lung cancer in smokers by comparing them with non-smokers. This study shows that non-smokers are not a homogenous group and should be subdivided according to the extent of previous exposure to indirect or passive smoking.

This work was suported by Grants-in-Aid for cancer Research from the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

References

1 Brunnemann KD, Adams JD, Ho DPS, et al. The infuence of tobacco smoke on indoor atmospheres. II. Volatile and tobacco specific nitrosamines in main-aid sidestream smoke and their contribution to indoor pollution. In: Proceedings of the 4th Foint Conference on the Sensing of Environmental Pollutants. New Orleans 1977. Washington: American Chemical Society, 1978:876-80.

2 Brunnemann KD, Hoffmann D. Chemical studies on tobacco smoke LIX. Analysis of volatile nitrosamines in tobacco smoke and polluted indoor environments. In: Waler EA, Griciute L, Castegnaro M, eds. Environmental aspects of N-nitroso compounds. (IARC scientifics publications No 19) Lyons : WHO, 1978:343-56.

3 White RJ, Froeb FH. Small-airwais dysfunction in non-smokers chronically exposed to tobacco smoke. N Engl F Med 1980;302:720-3.

4 Hirayama T. Prospective studies on cancer epidemiology based on census population in Japan. In: Proceedings of XI International Cancer Congress. Florense. Cancer Epidemiology and Environmental Factors, 3. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica, 1975:26-35.

5 Hirayama T. Epidemiology of lung cancer based on population studies. In: Clinical implications of air pollution research. Chicago: The American Medical Association, 1976:69-78.

6 Hirayama T. Smoking and cancer. A prospective study on cancer epidemiology based on census population in Japan. In: Proceedings of the 3rd World Conference on Smoking and Health 1975. Washington: Department of Health Education and Welfare, 1977:65-72. (DHEW Publication No (NIH) 77-1413.)

7 Hirayama T. Prospective studies on cancer epidemiology based on census population in Japan. In: Nieburgs HE, ed. Third International Symposium on Detection and Prevention of Cancer. Pt 1. Vol 1. New York: Marcel, Dekter, 1977:1139-48.

(Accepted 13 November 1980)

National Cancer Centre Research Institute, Tokyo

TAKESHI HIRAYAMA, MD, MPH, Chief of epidemiology division

以上平山論文の内容を日本語訳(翻訳: Google翻訳)とオリジナル論文をコピペさせていただきました。ソース

https://scielosp.org/article/bwho/2000.v78n7/940-942/#tab2

前の記事へ

次の記事へ